Nkhotakota, Malawi –The Dali family was once a happy household until Mrs. Dali developed obstetric fistula. Life as they knew it unravelled. Tension grew at home, and in the community. Whispers on her condition turned into stigma. People kept their distance from her, citing a foul smell from her continued leaking of urine.

The stigma reached its peak when Mrs. Dali approached a neighbour to borrow a pestle and mortar to prepare vegetables for dinner. The neighbour’s response was brutal. She told her outright that she might "contaminate" the utensils. Devastated, Mrs. Dali returned home in tears, recounting the incident to her husband.

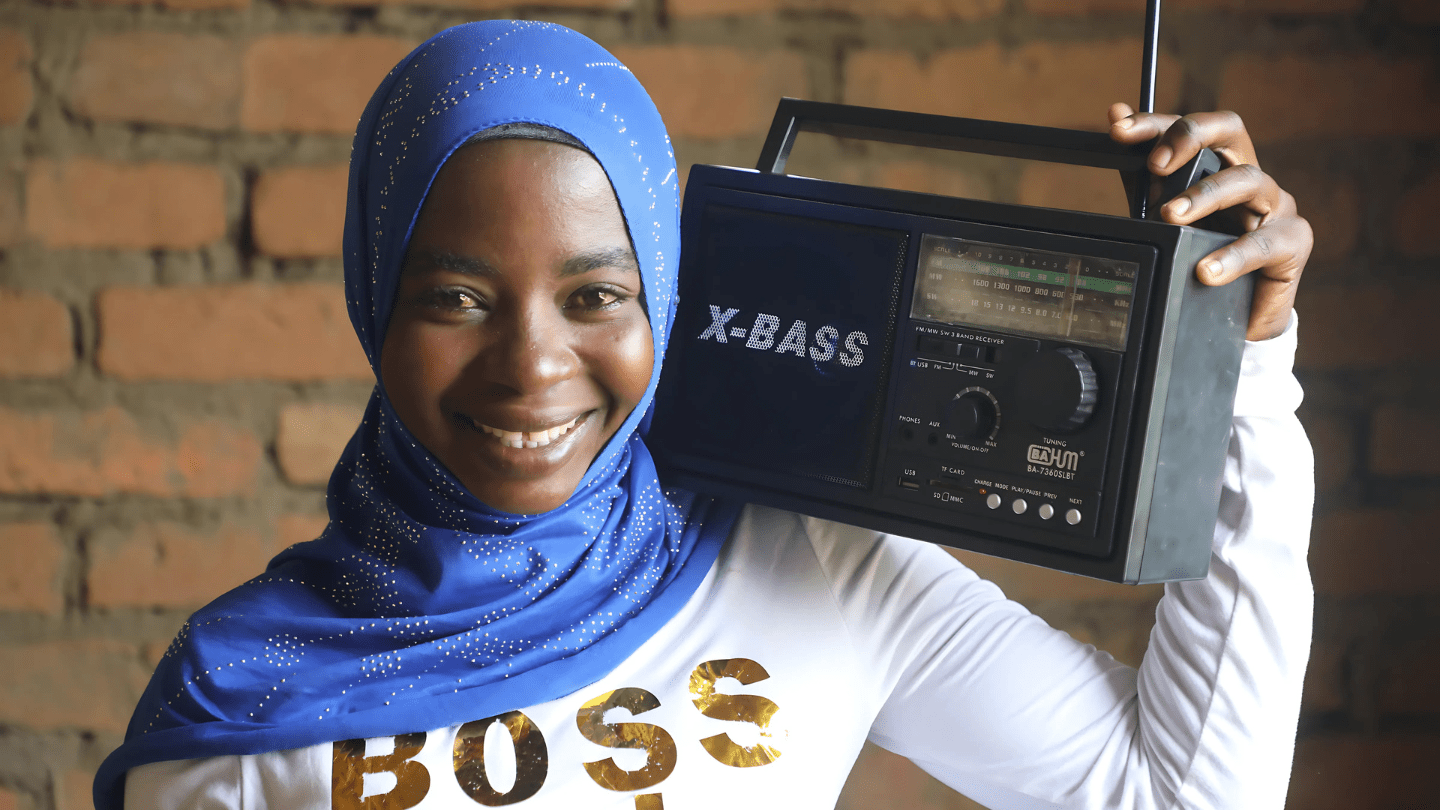

This heartbreaking scene unfolds in a drama series being aired by a local community radio station, and listening, are members of a radio listening club. Women in the audience are moved near to tears, while the men bow their heads in shame, reflecting on Mr. Dali’s failure to stand by his wife. The power of the interactive drama, broadcast from a small radio, is palpable.

As the play concludes, silence hangs in the air. The facilitator allows a moment for reflection before urging the group to stretch—a simple gesture that breathes life back into the room.

Today is a special session for Vintenga Radio Listening Club, based in Chief Simba’s Village, Nkhotakota. The radio listening club was established in 2024 under the Bridging Hope Project, supported by UNFPA with funding from the Government of Iceland. The club is one of the many formed in the district to educate communities on fistula prevention and treatment.

Implemented by UNFPA’s partner, Theatre for Change, the radio interactive dramas have broken long-held taboos, sparking discussions on issues once considered too sensitive to address.

Men Join the Conversation

“Since the group was formed, we’ve seen a major shift in how people talk about fistula,” says Adam Kalubya, the club’s secretary and an Agent of Change (AOC). “In the past, anything affecting private parts was treated as a taboo. Now, people are willing to engage.”

Chief Simba, a respected member of the group, is the first to respond to the drama. He condemns Mr. Dali’s failure to support his wife, emphasizing the responsibility men have in ensuring women receive care.

The conversation opens the floodgates.

“Mr. Dali should have taken his wife to the hospital,” says Tamandani Simba, another AOC. “They planned to have a child together, and while things didn’t go as expected, their baby is a blessing. His wife is not at fault for developing fistula.”

As discussions deepen, the radio announcer introduces a new segment—a live role-play exercise. The facilitator calls for volunteers, and hands shoot up. Farida Banda is selected to play the role of the neighbor’s husband, challenging his wife’s discriminatory behaviour.

On-air, Farida confronts the fictional wife’s reluctance to share utensils with Mrs. Dali. Despite resistance, she remains firm, advocating for compassion and understanding. When she returns to the group, she is met with thunderous applause.

I felt her behaviour wasn’t right. As women, we should uplift each other. You never know—tomorrow, it could be one of us facing the same challenge

Shifting Perceptions

Beyond the role-play, the session features an interactive quiz, drawing calls from far and wide. Encouragingly, men’s participation is growing, a fact not lost on the announcer.

“Fistula is often seen as a ‘women’s issue,’ which is why men tend to remain silent,” says Mustawa Mumba, the session’s facilitator. “But men hold the power in many households—whether a woman seeks treatment or not often depends on their support. That’s why we need more conversations like this.”

In Nkhotakota, gender-based violence, early marriages, and harmful cultural practices fuel high rates of obstetric fistula. A recent UNFPA survey revealed that only 30.8 percent of women in the district are aware of fistula, and a mere 6.3 percent personally know someone who has experienced it.

Yet, the tide is turning and the radio listening clubs are proving to be a catalyst for change.

“Radio has the power to challenge deeply ingrained beliefs and harmful traditions,” Mustawa says. “We still have a long journey ahead, but we are making progress. The most important thing is that we are all committed to defeating fistula—and we won’t stop until we do.”

Joseph Scott, Communications Specialist