Nkhotakota, Malawi – At just 17 years old, Sakina Mbamba’s dreams of a bright future were abruptly interrupted when she discovered she was pregnant. Overwhelmed with fear and uncertainty, she contemplated eloping to her boyfriend’s house. But before she could leave, her mother intervened.

“I was terrified of my mother’s reaction,” recalls Sakina, now 20, from Khutu Village in Nkhotakota. “I thought running away was my only option, but a friend I confided in told my mother, and she stopped me.”

Her mother’s disappointment was profound. As the only child in the family who showed promise for higher education, Sakina was her mother’s hope. While her siblings had only completed secondary school, she had excelled in her primary school leaving exams. But with the pregnancy, her education came to a sudden stop.

“I felt like I had let her down,” Sakina reflects. “She worked so hard to provide for my education, and I had to promise her that I would return to school after giving birth.”

A Health Crisis Unfolds

During her pregnancy, Sakina began experiencing sudden fainting spells. Initially, her mother attributed it to the heat and the pregnancy. But when the episodes persisted, even in cooler weather, concern grew.

A visit to the district hospital provided little relief.

“They told us it was anxiety and that it would pass after delivery,” she says.

However, when she went into labour, another episode struck—this time lasting for hours before she regained consciousness. Alarmed, the medical staff opted for an emergency caesarean section, fearing that another fainting spell during labour could endanger both her and the baby.

“The operation was successful, and I gave birth to a baby boy,” Sakina says.

But just two days later, a new nightmare began. She realized she had lost control of her bladder.

“I couldn’t stop wetting myself,” she explains. “My mother immediately alerted the nurses, and they inserted a catheter as a temporary measure.”

Days turned into weeks, but the condition persisted. Doctors kept changing the catheters, but the problem remained unresolved. Eventually, with no solution in sight, Sakina returned home.

“I became a prisoner in our own house,” she says. “I avoided friends, the market, and any social gatherings. The shame and discomfort caused by the constant wetting were unbearable.”

A Lifeline at Bwaila Fistula Centre

Hope came through an unexpected phone call from a relative who had heard about the fistula treatment program at Bwaila Fistula Centre in Lilongwe. Without hesitation, Sakina and her mother boarded a bus the next morning to Lilongwe.

“At Bwaila, they confirmed that I had obstetric fistula. The next day, I underwent surgery to repair it,” she recalls.

When she woke up the following morning, she felt something she thought she would never experience again—dryness.

It was like a miracle. I finally felt normal again.

Sakina stayed at Bwaila for a month to fully recover. By the time she was discharged, she was healed and ready to rebuild her life.

A Second Chance at Education

Determined to keep her promise to her mother, Sakina set her sights on returning to school. However, doctors advised her to wait six months before resuming studies, as the three-kilometre walk to school posed a risk of reopening her wounds.

By the seventh month, she was back in the classroom, re-enrolling in Form One. Despite the challenges—including the death of her baby—Sakina remained focused.

“I pushed myself, and I managed to perform well in my first term,” she says.

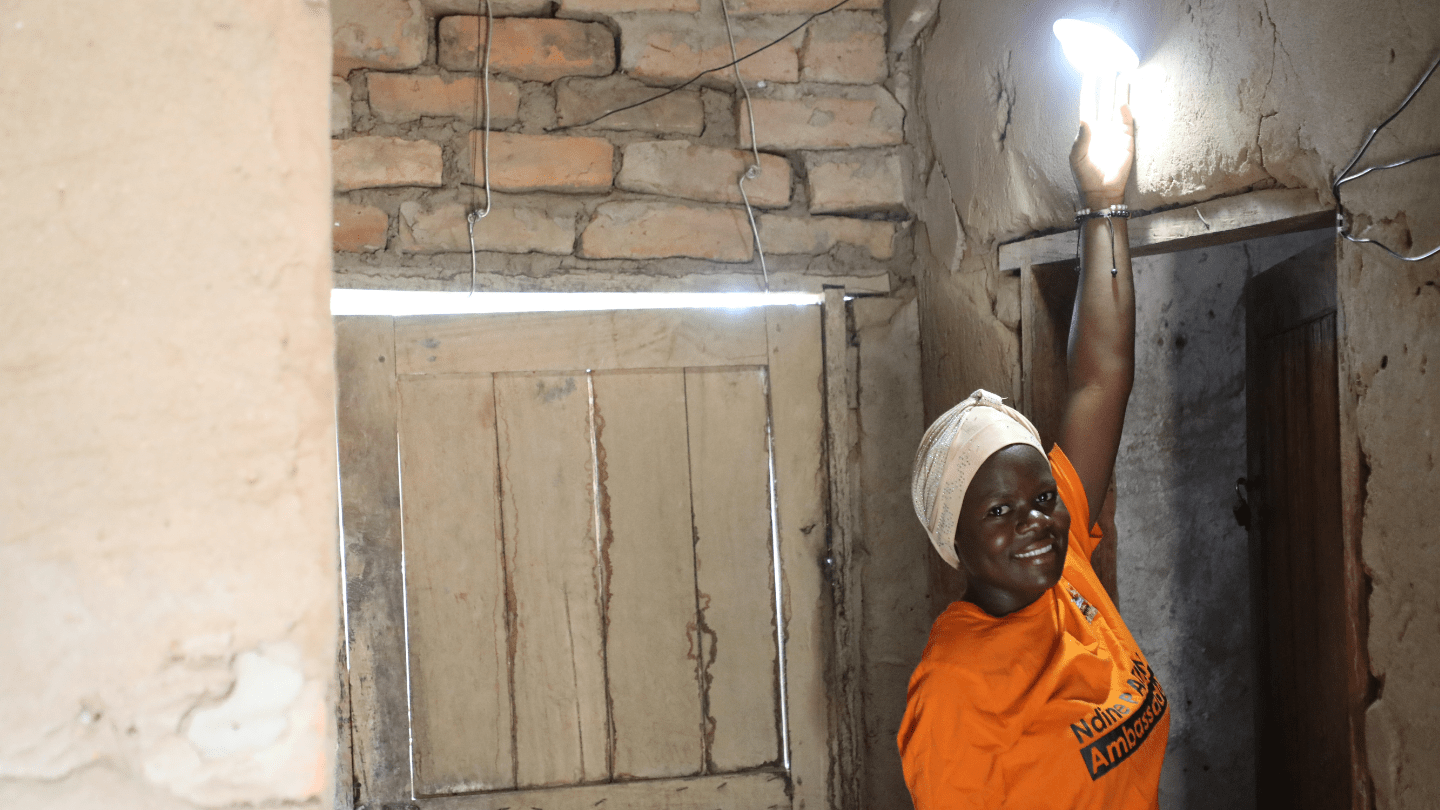

To help her reintegrate into the community and support her education, UNFPA, through the Bridging Hope project funded by the Government of Iceland, provided her with a sewing machine.

“Since I was in school, my mother attended the tailoring training in my place,” she explains. “The idea was for her to pass the skills on to me in my free time.”

Today, the sewing business is the family’s primary source of income. Together, Sakina and her mother make dresses, reusable sanitary pads, and bags, selling them at the local market.

“On a good day, we make around MK10,000,” she says. “That money helps us buy food, pay school fees, and purchase learning materials.”

Looking Ahead: A Future in Agriculture

With her health restored and her education back on track, Sakina is now setting her sights on an even bigger dream—becoming an agricultural specialist.

“We have plenty of family land, but we lack the skills to maximize its potential,” she explains. “If I graduate, I want to turn our land into a thriving farm.”

Joseph Scott, Communications Specialist