Nkhotakota, MALAWI— On a quiet Monday morning, Mphatso Chunga from Nkhotakota sat under a mango tree, just a stone's throw from her home, avoiding the sweltering heat. Her body ached after hours in the rice fields, but at eight months pregnant, she brushed it off as mere exhaustion.

But as the heat intensified, so did her discomfort. Sweat dripped from her brow, and an unsettling tightness gripped her abdomen. Something was wrong.

Her husband, noticing her distress, ran to alert the neighbours. Experienced elderly women quickly assessed the situation—Mphatso was in labour. Panic set in as her husband hurriedly fetched his bicycle, placing her on the rear carrier.

The nearest health centre was four kilometres away, but every jolt on the rough, gulley-filled road sent sharp waves of pain through her body.

“Our roads are in a terrible state and the bumps made the pain unbearable,” she recalls.

After an excruciating hour-long journey, Mpatso and her husband finally reached the health centre. But their relief was short-lived. After assessing her condition, the medical staff informed them that Mphatso needed an emergency caesarean section—a procedure only available at the district hospital, 30 kilometres away.

“They told me the baby wasn’t positioned correctly,” she says. “For a safe delivery, I needed surgery.”

Fortunately, an ambulance from the district hospital was present to collect other patients. Within moments, Mphatso was on her way. But tragedy struck before she could reach the operating room.

“The doctors told me the baby didn’t make it,” she recalls, her voice heavy with emotion. “It wasn’t the news I expected, but I had no choice but to accept it.”

A week later, Mphatso was discharged. But soon after returning home, she noticed something was wrong—she had lost control over her urine.

I started wetting myself. I didn’t understand what was happening.

At the hospital, doctors diagnosed her with obstetric fistula, a severe childbirth injury caused by prolonged labour.

“I had never heard of this condition before,” she says. “I was terrified. I felt like a child again, unable to control myself.”

Devastated, Mphatso returned home, only to face another heartbreak. Her husband, unable to cope with the smell of constant leakage, abandoned her.

“It was tough,” she recalls. “I couldn’t socialize or do any household chores. For eight months, I lived in isolation.”

Then, in late October 2024, a life-changing call came. The hospital informed her that she would be transported to Lilongwe for fistula repair surgery at Bwaila Fistula Centre.

“I told them I didn’t have the money for transport,” she says. “They assured me the funds would be provided. The next day, I received MK24,000.”

With renewed hope, she made the journey to Lilongwe, where the surgery was successfully performed.

“I kept checking myself to see if I was truly dry,” she says, a smile spreading across her face. “I never thought I would feel normal again.”

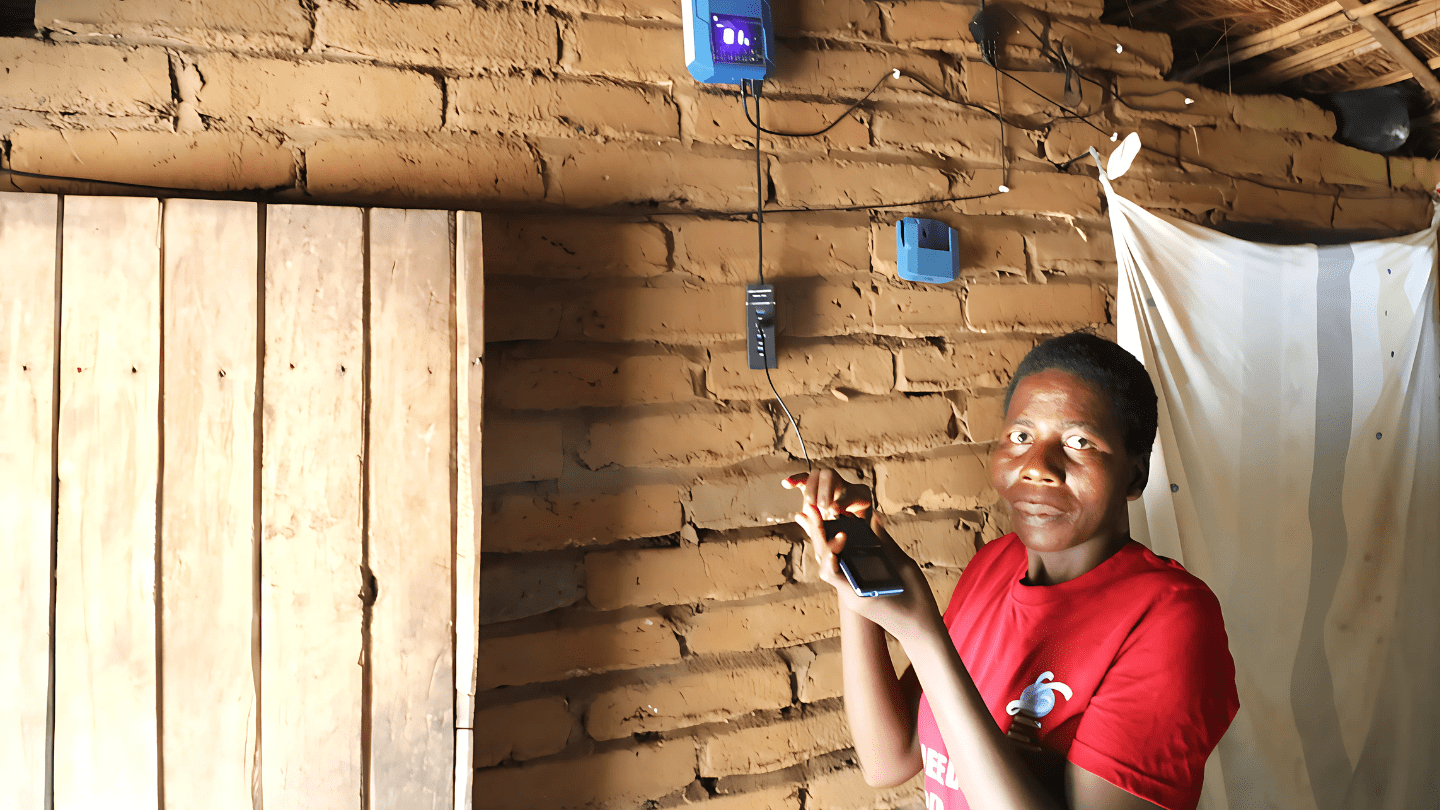

Mphatso’s treatment was facilitated by UNFPA through the Bridging Hope project, funded by the Government of Iceland. To support her reintegration into society, the project also provided her with a solar power system capable of running small electrical equipment.

“The solar package was a blessing,” she says. “I started a small business charging phones for people in my community.”

At MK150 per charge, she earns up to MK3,000 a week, enough to sustain her and her children.

“I haven’t resumed heavy work like farming yet,” she explains. “I need at least six months to fully recover. But this small business has helped me support my children. They are all in school, and I can afford their needs thanks to this opportunity.”

Joseph Scott, Communications Specialist